Emil Neufeldt, Chapter 1

In the summer of 1945, in a small town called Neuland, Germany, and elderly 71-year-old man stared helplessly at what had been his home. A couple months earlier, in March, he had left it in a hurry after hearing reports that the Soviet Red Army was soon to invade.

He quickly packed for practicality all of his clothing and whatever food he could gather, while his younger wife greedily grabbed her jewelry. He shoved it all into his Mercedes which he hadn’t been able to drive for years, since 1940. But he’d been saving up his gasoline rations and would use what little amount he had to get south to Czechoslovakia, and hopefully safety.

Now, months later, the elderly man and his middle-aged wife staggered back home. His Mercedes had been confiscated by a fleeing German officer, but still the older man had hope, because he had a large house, with extensive gardens and orchards and chickens—plenty of food to feed his daughters, their husbands, and his grandchildren once they could come back again . . .

Except he didn’t find his home.

He found instead a crater left by a bomb, surrounded by piles of rubble. The crater was filled with water, and floating on the water was his granddaughter’s mattress. Lying on it was a German soldier, dead.

The elderly man stared, realizing that his plans for reuniting his family, currently fleeing west in various directions ahead of the Red Army, were not going to happen. There was no home for them to come home to.

He gazed helplessly at his complete ruin, but not hopelessly.

His looked wearily at the details of the rubble around him, hoping for something salvageable in the remnants of a once-grand house that held hundreds of books and a two-story high music room and beds to spare for visiting grandchildren.

In the rubble he noticed bricks, still intact, and he knew what he had to do.

While his wife stared in despair, then in confusion, Emil Neufeldt stooped and picked up one brick, then another. He carefully brushed them off and stacked them neatly in a pile to the side of the rubble. Then another, and another.

He had to rebuild for his family. There were no other options.

This is the story of Emil August Neufeldt, and of his granddaughter, Yvonne Neufeldt. (Written by his great-granddaughter, Trish Strebel Mercer.)

Emil’s early years

An article written just four short years later in 1949 about Emil Neufeldt, age 75, would have made him rather uncomfortable. The writer, Paul Thomas, a colleague in Neisse who admired him greatly, got a few things right about Emil: he was a very successful engineer for the sugar industry and in charge of the construction of the machinery at Weigelwerk AG, a factory which distributed his machines to more than 50 sugar plants throughout the region. He frequently traveled throughout Germany and Poland to oversee installation of that machinery and, in the words of Herr Thomas, was “honored highly by friend and foe alike.” At his funeral “a large crowd of mourners laid him to rest at the Neulander Cemetery.” (Neisser Heimatblatt, No. 112, “Industry in Neisse: in Memorial of Engineer Emil Neufeldt”).

However, Herr Thomas got a few details wrong. The facts of Emil’s life were actually more interesting than Herr Thomas or anyone else really new.

And also more tragic.

Herr Thomas was correct that Emil was born in Stronau, Kreis Bromberg, on Nov. 27, 1873. At the time it was part of Prussia but now it’s Bydgoszcz, Poland. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kreis_Bromberg.

To say where Bromberg “is” is a rather complicated thing, so to clarify where Emil was “from” takes some explanation. For Americans, the idea that your town many have a different name, language, and even be a different country several times during your life may seem quite strange, but it was reality for Emil. No city in Eastern Germany/Western Poland is easily defined as to where it is because of shifting empires and suddenly new countries.

Bromberg or Bydgoszcz?

To simplify, here’s where Bromberg “was” since the late 18th century:

- In 1772 Bromberg was part of the Kingdom of Prussia (Prussia was its own German-speaking empire for two hundred years, starting in 1701 and ending after WWI in 1918).

So it was Bromberg, Prussia. - But starting in 1803, Napoleon was trying to create his own empire, and he took over Bromberg in 1807, thanks to the Treaty of Tilsit.

So then it was Bromberg, Napoleonic Poland. - But just eight years later, Napoleon was defeated and Europe redrew the boundary lines again. Because of the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Bromberg was once again part of Prussia: Bromberg, Prussia.

- In 1848 Bromberg—still part of Prussia—was assigned to be part of the province of Posen.

- Then in 1871 the German Empire was created, unifying the Kingdom of Prussia with 26 other states to create one country. Emil was born in a country that was only two years older than he was, which means his four older siblings who, while born in the same city as he was, were actually born in a different country.

Bromberg, Prussia was now Bromberg, Germany - In 1918, after WWI, part of Posen began to revolt. In this area were many Poles, and they didn’t appreciate German rule. Battles erupted throughout Posen, but Bromberg never fell. However, the Treaty of Versailles signed in the summer 1919 to punish Germany for its contributions to WWI gave Bromberg, which was filled with mostly Germans, to Poland. By winter of 1920, Poland had full control of Bromberg. Between that summer and winter, most of the Germans left for “safer” areas. By January 1920, Bromberg was Polish.

Bromberg was now Bydgoszcz, Poland. - This new rule lasted only until 1939, when Hitler invaded Poland and retook and renamed Polish cities.

Bydgoszcz was again Bromberg, Germany. - Six years later, in 1945, the Soviet Red Army invaded, the land became Poland again.

Bromberg, German, was now, and still is in 2021, Bydgoszcz, Poland. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kreis_Bromberg.)

In the span of Emil’s life, Bromberg was part of four countries and had six name changes. Depending upon how one refers to the city, you can guess to some of the history they were living at the time.

When Emil was born in Bromberg, Germany, just two years after the Germany Empire was established, the entire region was well-populated with over 700,000 residents (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bromberg_(region)) fairly evenly split between German and Polish descent. Emil grew up bilingual in both German and Polish, which wasn’t as common as one might think, despite the fact that both languages were common in the area.

There remained some occasional animosity between the Germans and the Poles who shared the same land but believed it should belong to their country, and that the “others” living there should leave. However, most people had no problem with the “others.” In fact, Emil’s father was German and his mother was Polish, so there was clearly some crossover and happy marriages between the two nationalities.

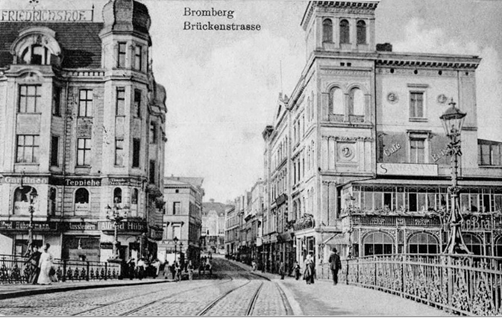

Bromberg in an 1890s postcard

Bromberg in an 1890s postcard

Emil’s family

Emil’s father was a forest ranger, and his parents’ greatest hope for him was to also become a forest ranger, or even a farmer, as had been the family tradition. Emil had four older siblings—three brothers and a sister who were 13, 11, 10, and 6 years older than he was. Their occupations are unknown, but it’s possible that they were involved in the family farm or took after their father roaming the forests.

In Bromberg at Emil’s time, there was a society to improve the gardens and town squares. From 1832-1898, the Society for the Beautification of the City of Bromberg and its Environs was active in making gardens and planting trees (https://visitbydgoszcz.pl/en/explore/visitor-itineraries/2907-green.)

But Emil, the youngest son, was interested in something else entirely, and it greatly alarmed his parents. Emil wanted to go into manufacturing and engineering.

Nowadays, in the 2020s, engineering is a great occupation, but not so in the 1890s. Emil’s father, Ludwikg Neufeldt (very German) and his mother Auguste Idzigowska (very Polish) were worried for their youngest child. In the 19th century, manufacturing meant working in factories which were notoriously unsafe, dirty, and noisy. But this was the middle of the Industrial Age, and increasingly it seemed that factory life was the only way to make a living. Such a completely opposite line of work from farming and forestry.

But despite his parents’ pressure to stay out of the factories, Emil just didn’t feel the forests or farms in his blood. He didn’t jump directly into working at a factory, though. During the 1890s he was, at one point, in the army, as the only photo of him in his youth shows. There wasn’t any war at the time, but all young men were expected to provide two years’ of military service for their country.

Emil in the 1890s

Emil and Mariana

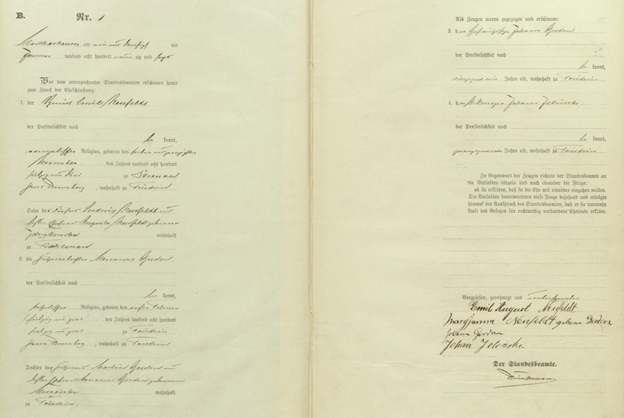

Sometime after this military service he married the love of his life, Marianna Gordon, in 1896. He was 23 years old, and their wedding day, Feb. 1, was also her 24th birthday. She had been born in the area, in Trischin, Posen, when it was part of Prussia.

Mariana was the second oldest of six children, and her parents were Martin Gordon and Marianna Murawka. Her father was a “cottager,” according to their marriage certificate, which likely meant he owned a small piece of property and farmed it. So if Emil didn’t become a farmer, he at least married a woman who had been raised on a farm.

Because of Mariana’s father’s non-Polish-sounding name—Martin Gordon—he may have been of French or British descent. But her mother was solidly Polish.

Mariana was raised speaking Polish first, German second, so she and her new husband were conversant in both languages. Mariana always had a slightly Polish accent to her German.

Emil and Marianna married in Wtleno, now in Poland, which was just a few miles north of Bromberg, and began their family soon after. They happily settled in Bromberg which, in the late 1890s, was still part of the German Empire.

Marriage certificate of Emil and Mariana, in possession of Barbara Goff.

In January of 1898, less than two years after their wedding, their first son was born: Paul Hilarius.

A year and a half later their first daughter arrived, in August of 1899: Helene, who they called Lene (or Lena). Shortly after his second child was born, Emil’s career began to shift.

Emil’s career

In 1900, when Emil was 26, there are records of him working in a factory, just as his parents had feared he would. He was employed in the sugar industry, as the articles written near the end of his life proudly stated.

At the time, sugar beet production was a major agricultural industry in Germany and Poland, and there were dozens of factories in the region squeezing the sucrose out of the beets to dry out and sell as sugar throughout Europe. Imported sugar cane from Hawaii was expensive, so it was a great boon that sugar beets thrived in Prussia/Germany.

“[T]he Prussian chemist Andreas Sigismund Marggraf [in 1747] succeeded in proving that the sugar in sugar cane also occurs in beet[s] – and with this, a fascinating success story began.” (https://www.suedzucker.de/en/company/history/history-of-sugar).

The trick was to get that sucrose in the most efficient way.

Enter Emil. What he was doing between completing high school at age 18 to age 26 is unknown aside from his military service and marriage, but the writers of the articles assumed that he had graduated from college and began his long and illustrious career in the sugar industry right after that.

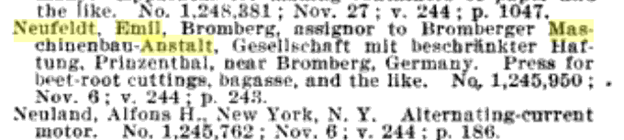

By the end of his life, Emil was known and heralded in several countries as a great inventor and engineer, and over several decades he created and patented many inventions which improved the sugar industry (Thomas). One patent was even recorded in America from when Emil was living in Bromberg.

Official Gazette of the United States Patent Office, Volume 244

However, there’s a problem with this glowing report of Emil’s rise in the sugar factory: he never attended college. That the articles written later in his life proclaimed that he was a college graduate was a source of silent embarrassment for him, but he never said anything about those mistakes.

His parents hadn’t wanted him to attend college. Perhaps they couldn’t afford it, or maybe they thought they could pressure him to follow the forest-farming advocations they wanted for him. But for whatever reason, he was simply working in a sugar factor and then became one of its greatest innovators.

So how did he become a great inventor and engineer?

Natural talent.

In 1900, according to one article, he was installing a newly delivered piece of machinery, a schnitzelpresse (it pressed sugar beets, not schnitzel), in a sugar factory in Niezychowo, now in Poland. But the machinery didn’t work. Engineers tinkered with it, tried it again and again, and still it failed to perform as it should (Neisser Zeitung).

Emil, the installer, was watching and analyzing their lack of progress. Then, when they couldn’t figure out what more to do, he made some recommendations. And with those modifications, the schnitzelpresse finally worked. That’s what started his career as an engineer and designer in the sugar industry (Neisser Zeitung).

Soon he was hired on as a schnitzelpresse engineer and was hugely successful, with only his on-the-job training to guide him. Clearly he had a gift and knew he wasn’t destined for the forests or farms.

His first patent for machinery came about a dozen years later, in 1912, and he kept inventing and earning patents and revolutionizing the sugar industry in Germany and Poland until he was 67 years old, in 1941. Even then, he didn’t stop working for the industry.

And all without a college education. He was a completely self-made man, keenly observant and a natural trouble-shooter. What he lacked in education he more than made up for in resourcefulness and sheer hard work. During his career of over 40 years, he was sent to 54 sugar factories in the region to install his inventions, see what could be improved, then design yet something else to increase the efficiency of the sugar industry.

Emil and Mariana’s family

But back to his growing family. In December of 1902, his second daughter arrived, Hedwig Klara, who they called Hedel.

Another two years after that, Paul finally got a little brother—Roman—who died when he was only a toddler, in 1906.

Another son also followed, but died either at or shortly after birth, and was never named.

In light of the tragic loss of two of their three sons, Emil and Marianna were grateful for the three of their five children who did survive, and lavished love and attention on them. They raised their family in Bromberg, Emil beginning his career as an engineer when he was a father of two young children.

Paul Hilarius Neufeldt

The oldest, their son Paul, was a talented and mischievous boy. He had a great propensity for getting dirty, to the point that when the young family took their Sunday strolls, they learned to set little Paul by the front door in his underwear and dress him only at the very last minute before leaving the house. Even then, he still found ways to get completely filthy which, because Marianna believed in keeping a clean house, was a frustration for her. As he grew older, he continued to not care too much about the state of his bedroom, or his school books, or any of his possessions. Messes were everywhere around Paul.

However, he was a gifted musician, and learned to play the violin well enough to perform solos in their local cathedrals. He was also skilled in math and science. He was bright, very sensitive, and well-liked, with friends everywhere he went. Emil and Marianna had great hopes for their son.

The Great War

Then came World War I, where Paul served for a time in Russia. While he came home safely, the fallout from that war was going to affect the Neufeldts for many years to come.

The First World War was also ironically known at the time as “the war to end all wars” and “The Great War” because it was pretty big and all encompassing, until an even larger war seemingly dwarfed it in importance. Still, up to a staggering 20 million soldiers were killed during those four years of war, and another 21 million more were wounded (https://online.norwich.edu/academic-programs/resources/six-causes-of-world-war-i).

To put it simplistically, the war was officially started when a 19-year-old shot the next-in-line of another country. The action was just an excuse for many of Europe’s countries to finally fight it out. They had been in competition with each other for some time, trying to outdo each other with armies, armaments, and established colonies, all in pursuit of showing which country was supreme in the region. In other words, they were group of schoolboys who had been talking trash for quite a while and were circling each other in the playground, waiting for someone to throw the first punch and finally get it all going.

Which empire was going to be THE empire? There were several by 1914.

“No, We’re the best country!”

Germany, for example, had become the German Empire in 1871 by unifying its 27 smaller kingdoms. But it wasn’t the only country trying to expand.

During that time England was growing its British Empire all over the world, and France had been toying with increasing its empire as well since Napoleon had started them on that track. Britain and France were snatching up and ruling territories in Africa and Asia, and new empires like Germany wanted in on the game as well, taking lands in Africa for themselves. These vast regions had great wealth the European countries wanted to exploit, and as expected, the native countries and the invading imperialists often didn’t get along.

There were always tensions, especially if Germany was trying to grab land that France was after in a remote part of Africa. Bigger was better, and many countries were out to prove they were better (https://online.norwich.edu/academic-programs/resources/six-causes-of-world-war-i; https://www.thoughtco.com/causes-that-led-to-world-war-i-105515).

They were also arming themselves in the years leading up to 1914, trying to show who was the strongest boy on the playground. Great Britain and Germany were out to prove who had the biggest warships and the largest navy, while Russia was trying to outdo Germany’s size of army, and succeeding (https://www.thoughtco.com/causes-that-led-to-world-war-i-105515). This drive for militarism focused European countries on not just showing off their manpower and weaponry, but gave them hope to show its effectiveness as well.

Protect the “little brothers”

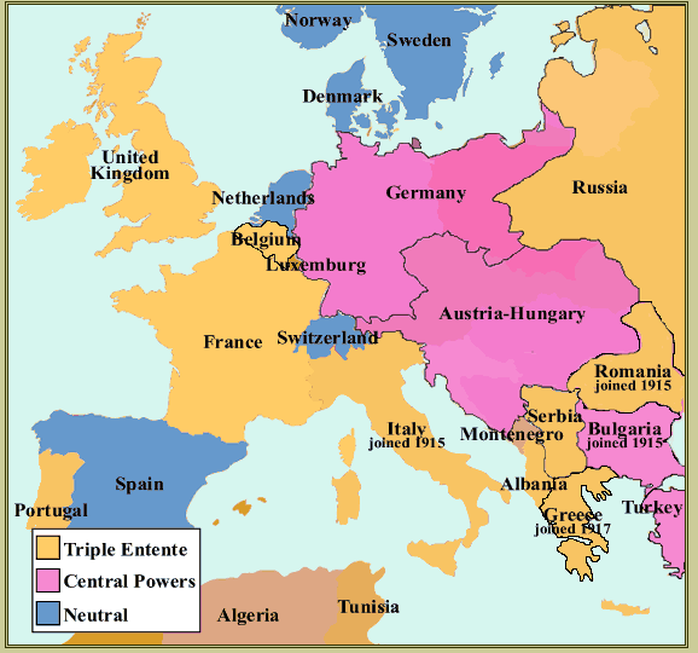

Since many countries were expanding their territories and forces, smaller countries realized it would be a good idea to pair up with the stronger countries, in case any fighting broke out. Alliances were created to try to keep balance of powers in Europe and ensure the “little brothers” were protected. It also meant that if someone attacked one country, they attacked the entire alliance. By 1914 there were several countries looking out for each other. Allied were:

- Russia and Serbia

- Germany and Austria-Hungary

- France and Russia

- Britain and France and Belgium

- Japan and Britain (https://www.thoughtco.com/causes-that-led-to-world-war-i-105515)

It’s easy to see how an attack on one country, say Britain, would draw in several other countries to fight you in Britain’s behalf. Suddenly you’re facing also France, Belgium, and Japan.

The empire we remember only because of WWI

The Austro-Hungarian Empire allied with Germany in 1879 and 1882 because they were worried about Russia trying to expand into the Balkan region, and they were also concerned about the French growing too powerful in Europe. Later Italy joined them—what then became known as the Triple Alliance—because they also didn’t like how France was trying to gain more influence (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Austria-Hungary). In the middle of Europe, these allied countries hoped to keep the countries on either side from expanding.

With countries gaining power and territory, there also arose a strong sense of nationalism in Europe—pride in one’s own country, and resentment toward other groups living in your country. This was often the case in Germany, and in places like Bromberg where the Neufeldts lived. Such regions weren’t just German, they were also populated with Poles who resented that a few decades before the place was theirs. Borders were frequently redrawn in Europe, with people discovering that the growing empire of one country now meant they were no longer their nation but subsumed into someone else’s.

Where’s Bosnia?

That’s what happened with the Austrian-Hungarian empire, also trying to establish itself during these years. Starting in 1867, about fifty years earlier, the countries of Austria and Hungary combined to rule together. It was a large area geographically, second only to Russia, and larger than the German empire, although Germany had more citizens. About 20 years later, the Austrian-Hungarian Empire took over Bosnia and Herzegovina, which the Bosnians did not appreciate at all. All throughout Europe were little pockets of angry citizens frustrated that their nation wasn’t a nation at all (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Austria-Hungary; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Serbia).

And Serbia?

Another nationality not happy with the Austrian-Hungarian empire were the Serbians. They had become their own kingdom in 1878, recognized as such by other countries, and soon after found themselves in a war with Bulgaria in 1885 and lost the territory they were hoping to win in that war (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Serbia). At the time, the Austrian-Hungarian Empire had come to defend Serbia against Bulgaria, and Bulgaria quickly retreated, leaving their border lines exactly as they had been before the war (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Serbia).

Serbia continued fighting to increase their kingdom and their influence over the next few decades, but the Austrian-Hungarian Empire was holding part of their lands. A radical group of Serbian officers wanted to unite all Slavs, just as Italy had recently united all Italians into one country. This revolutionary group, calling themselves Black Hand, formed in 1901. By 1914 they had committed a few assassinations and were organized enough with hundreds of members hoping to unify all Serb-inhabited lands, including those held by the Austro-Hungarian Empire. One of the leaders of Black Hand was upset that Archduke Ferdinand, who was expected to be the next ruler of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was trying to pacify Serbians about their condition. Black Hand didn’t want their fellow Serbs pacified, but radicalized. They wanted revolution, not peace. So they plotted to have assassins waiting for the Archduke’s next visit to Sarajevo (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Hand_(Serbia)).

A convenient excuse for a war

On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his Sophie drove through the city in an open car, and the citizens lined the road to watch the grand parade which had very little security.

One assassin hiding in the crowd threw a small bomb which bounced off the convertible roof and exploded against another car with minor damage. Three more assassins in place further down the road tried to take the Archduke out, but another man couldn’t get his small bomb out of concealment in time, police were too close to another assassin, and yet another chickened out and ran off. Only by sheer coincidence because the driver took a wrong turn, the Archduke’s car pulled up right next to the last assassin, Gavrilo Princip, who immediately drew his gun and shot both the Archduke and his wife, who died a few hours later from their injuries ( https://www.thoughtco.com/assassination-of-archduke-franz-ferdinand-p2-1222038).

This event—the tensions between Serbia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire—was considered the catalyst for The Great War.

But interestingly, not immediately.

The assassination no one really cared about, except . . .

In fact, no one really cared too much that the Archduke was dead. In Vienna, Austria, the newspapers didn’t even immediately report it, because their Archduke had been a bit of a problem for the government, and they were quietly relieved he was gone. His uncle and cousin were to have been the next in line, but had died, leaving Franz Ferdinand next to take over the empire.

But no one liked him. He had married “beneath” him and the children he and his wife Sophie had were barred by the empire from becoming the next emperors of Austria-Hungary. With Franz Ferdinand out of the way, the leadership of Austria-Hungary could become something else. The only one sort of upset by the assassination was Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany, who had been trying to gain Franz Ferdinand as an ally. The assassination itself wasn’t a world-changing event. It was hardly even noted (https://www.thoughtco.com/assassination-of-archduke-franz-ferdinand-p2-1222038).

Except that it was incredibly convenient, and an assassination should never not be exploited.

This was the perfect excuse for Austria-Hungary to invade Serbia, since they’d been wanting the land the Serbs held. And because everyone in Europe was allied with everyone else, and had armies and navies and munitions and national pride just waiting for that first punch to be thrown, a European-wide war, which spread later to America and Asia, was the perfect stage for every country to show what it was made of, and ultimately decide who was the greatest power (https://www.thoughtco.com/assassination-of-archduke-franz-ferdinand-p2-1222038).

First Austria-Hungary waited to make sure Germany would support them, because Austria-Hungary didn’t feel ready for an all-out war on their own (https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-i/outbreak-of-world-war-i).

A month after the assassination—and with Kaiser Wilhelm’s “blank check” support—Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. Then Austria-Hungary braced for what they knew would come next: Russia. It took only a week for Russia, then France, Belgium, and Great Britain to declare war against Austria, Hungary, and Germany (https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-i/world-war-i-history).

The Great War was finally on.

In many ways it was a messy, useless war. By the end of the four years, and tens of millions of deaths, the Austro-Hungarian empire was dissolved by its enemies. Soldiers engaged in years’ long battles in deep trenches dug all over France and Belgium, fighting for one piece of land with guns, grenades, and poisonous gas, only to gain a few hundred yards to the next trench (https://www.history.com/news/life-in-the-trenches-of-world-war-i). That was on the Western Front.

Paul the Lieutenant

The Eastern Front was different, and that’s where Paul Neufeldt found himself as a teenager. As with many young men, Paul was sent to war and served as a young lieutenant (likely a 2nd Lieutenant https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_Army_(German_Empire)#Warrant_Officers_and_Officer_Cadets). He would have been 16-20 years old during those years of the war, so he probably served toward the end of the war. Since he was a young officer, probably taken from the university he was attending, he likely served around 1917 when he was 19. He was on the Eastern Front in Russia for a time as a cavalry officer, until Russia left the war in 1917.

It may sound unusual to us in the 21st century, but making a 19-year-old college student a lieutenant in the army was rather commonplace.

He may very well have been part of these troops who, as if fighting an ancient war, rode horses and carry lances, but because of modern warfare also wore gas masks, as if in a modern steampunk story.

(Photos downloaded from https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/german-cavalry-lances-1918/)

While Germany’s cavalry started off small—only one division at the beginning of the war against Russia’s 37 divisions, the cavalry quickly grew to hold back the Russians (https://weaponsandwarfare.com/2020/07/05/wwi-german-cavalry-on-the-eastern-front/). Paul was likely fighting for Germany when the calvary was larger.

At the beginning of The Great War, Russia had 140,000 cavalry troops on the Eastern Front, but many were converted to infantry troops later in the war (https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/cavalry).

The same thing happened with the German cavalry. While they quickly built up to 11 divisions, as the war continued, the amount of available horses declined because war takes its toll on animals, and because of the fighting, farmers weren’t able to breed and raise more horses. Many of the cavalry groups had, out of necessity, become foot soldiers.

By the end of World War I, there were only three cavalry divisions left on the Eastern Front, one which may have been Paul’s. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_cavalry_in_World_War_I).

Gas warfare

The reason for the gas masks is because WWI was the first time gas was created and used as a part of warfare.

Starting in 1915, the German army created chlorine gas which, launched into the trenches, settled down and suffocated the allied soldiers. France and Britain quickly started making their own poisonous gasses, and when the Americans joined the war in 1917 they, too, began making chemical weapons. Mustard gas was the worst and most common, created first by the Germans in 1917 to blister eyes, skin, and lungs, and killed thousands of soldiers (https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/germans-introduce-poison-gas).

But almost as quickly as these gases were created, so were highly effective gas masks. If a soldier got his mask on in time, the gas passed by him with no danger (https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/germans-introduce-poison-gas).

Horses, however, didn’t have too many masks, so wherever gas was used, horses—if present—often didn’t make it. In fact, eight million horses, donkeys, mules, and dogs died in WWI (https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/chemical-warfare-hell-even-horses-needed-gas-masks-during-world-war-i-50232).

Eventually some gas masks were created and used for the pack animals and even pigeons who carried messages, as much as possible (https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/chemical-warfare-hell-even-horses-needed-gas-masks-during-world-war-i-50232).

Little wonder that the cavalry began to diminish and soldiers had to continue on by foot.

End of war for Paul

When Paul returned from the Eastern Front, probably in 1917 at age 19, his feet and legs were in a very bad condition. Emil had to help him pull off his boots, which he had worn for at least several days, if not longer, to reveal that his feet and legs were severely infected and covered with bites, likely from lice.

Many men on the Eastern Front suffered from typhus carried by lice (https://microbiologysociety.org/publication/past-issues/world-war-i/article/typhus-in-world-war-i.html). Lice, typhus, and all kinds of maladies were among soldiers in WWI. They endured horrendous living conditions with no ability to clean up or change clothes for up to months at a time.

Few men returned home without some kind of infection or infestation. Paul was relatively fortunate he wasn’t worse off when he finally returned home, although he was quite miserable until he eventually healed.

The Great War ended in November of 1918, with Germany losing and the Austro-Hungarian empire collapsing. Life slowly started to get back to normal, but serious problems were in line for Germany, who received the blame for the war even though Austria-Hungary started it. But since the empire was gone, the next country to blame was Germany.

In the schoolyard fight that was World War I, the first to throw the punches, Serbia and Austria-Hungary, had been knocked out and dragged away. The last instigator standing was Germany, and the rest of Europe wasn’t about to let it sulk away without one last major hit.

Paul’s education

Until those punishments came for Germany, Paul was fortunate to be able to continue with his college education after the war, something Emil wished he could have done as a young man.

Because of the pressure Emil’s parents had put on him to be a forester, he was sure to never put any kind of pressure upon his own children as to what they should do with their lives. What they wanted to become, they could become.

Even so, Paul followed in his father’s footsteps to continue studying engineering in college, eventually going to graduate school in Mittelwalde/Saxony to complete a higher degree in mechanical engineering.

Leaving Bromberg

The Neufeldts loved Bromberg, but in 1919, after WWI, the situation changed. The Treaty of Versailles was intended to punish Germany for its involvement in the war, and one of the many provisions was that areas of Germany be handed over to Poland. This was the fate of Bromberg, along with many other cities. There had always been tensions between the Germans and the Poles, and The Great War exacerbated all of that.

It seemed that all of Europe was out to punish Germany for its participation, and the Poles living in that area of Germany saw their opportunity.

Near the end of December 1918, there was an uprising of Poles against the Germans in the province of Posen, where Bromberg was. But while the Poles took over some areas, Bromberg remained under German control.

Less than two months later, on Feb. 16, 1919, fighting ended because of an armistice between the two nationalities. Germany was ordered to give over Bromberg to Poland as part of the Treaty of Versailles, even though Bromberg was mostly populated by Germans. This was decreed on June 28, and just five months later, by November 25, 1919, plans were made to move all Germans out of Bromberg into evacuation facilities, which would certainly not be 5-star hotels.

By January 10 of that winter in 1920, all state buildings were cleared out of Germans and handed over to Poland. They had less than a month to complete all handover of lands and buildings. On Jan. 19, Bromberg was then officially Bydgoszcz, Poland. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kreis_Bromberg)

As soon as the Treaty of Versailles was signed, Emil and Mariana knew they needed to leave. Even though Mariana was Polish, her husband and children were German, based on their primary language of choice. Conflict was coming, and they knew they should leave Bromberg for somewhere more German.

They left in 1919 ahead of the handover to Poland. One of the articles written about Emil put it this way:

“Because of the deep feeling he had for Germany, he left Bromberg in 1919 [just before the official transition occurred] when it became Polish, and he joined the Weigelwerk in Neisse, Germany” (Thomas).

Again, the author didn’t get it quite right. For Emil’s part, there was no great love for Germany (the author of the article was solidly German and devoted to the Fatherland), just concern about his family’s safety.

A newspaper article written in 1943 did, however get the right spin:

“In 1919 Mr. Neufeldt was forced to leave Bromberg” (Neisse Zeitung).

Fortunately Emil had somewhere to take his family. A lot of Germans didn’t. The Neufeldts headed 250 miles south into Germany. Emil and Mariana dearly loved Bromberg and were disappointed to leave it. They headed to Neisse simply because the factory there—the Weigelwerk AG—gave Emil a great job offer he couldn’t refuse.

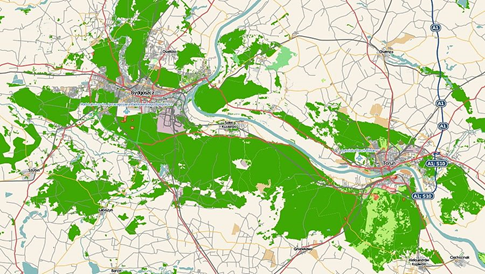

Bromberg to Nysa, driving distance in 2021

Seeing the political situations changing because of World War I, Emil also realized the move was the best thing for his children who were becoming young adults. In 1919, Paul was 21, Lene was 19, and Hedel was 17, and soon they would be looking for spouses. It’d be safer for them to find German spouses, rather than Polish.

Still, Emil’s heart remained in Bromberg/ Bydgoszcz, and he took his family to visit as often as possible. As a traveling engineer, he stopped there whenever he was in the area, later sending postcards home during his travels.

Germany’s punishment

The Treaty of Versailles brought all kinds of changes to Germany, intending to punish the country for its participation in The Great War. The treaty claimed that Germany started the war (since Serbia and Austria-Hungary were no longer players) and demanded enormous amounts of money to pay off the damage to the rest of Europe because of it (https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-i/treaty-of-versailles-1).

The punishment was staggering:

- surrender 10% of its territories and all overseas lands;

- Germany’s army and navy severely reduced;

- accept full responsibility for the start of the war (since there was no Austro-Hungarian empire to blame); and,

- pay for it all, to the modern equivalency of $33 billion.

No one really expected Germany could pay that, and that was part of the punishment—to keep Germany in poverty and powerless (https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-i/treaty-of-versailles-1).

In these conditions, Emil and Mariana were beginning in a new home, in Neisse Germany. If this was a good move for the family would soon–and forever–be up for debate. (Chapter 2 coming soon.)